Every fall, the Idaho Heritage Trust Board gathers in a different corner of the Gem State to meet with local preservationists, tour various sites of historical importance, and develop a better understanding of the plans, needs, and goals of each community we visit.

This year took us to Salmon and the beautiful Lemhi Valley. Of the many incredible places we visited and stories we heard, Yearian Ranch, home to the Sheep Queen of Idaho, left an indelible impression. From the stunning views and picturesque pastureland to the big house with its unique combination of sandstone and wooden construction, the sense of place is truly magical. The home is chock full of artifacts, family heirlooms, and keepsakes that help tell the story of Emma and Thomas Yearian, who’s joyous music you can almost hear echoing through the walls of their home.

In her incredible life, Emma Yearian wore many hats. At various points, she was a teacher, musician, storyteller, entertainer, adventurer, mother, politician, entrepreneur, and rancher. Known as ‘Big Mom’ to her children and grandkids and ‘The Sheep Queen of Idaho’ to everyone else, join us as we share what we learned about Emma Russell Yearian.

—————-

Emma was born to the Russell family on February 21st, 1866, in Leavenworth, Kansas. The Russells soon moved north to Illinois, where she would attend high school and go on to earn her teaching certificate from Southern Illinois Normal* College in 1883. She then headed west to find her place in the world. Emma spent a couple of years as governess for a family near Salmon, then spent two years teaching in tiny schools throughout Lemi Valley, which were often only a single room and built from logs.

During this time, Emma became quite in-demand for her piano playing prowess, attending dances and keeping the crowds happily tapping their toes. She became acquainted with a young fiddle player and cattle rancher by the name of Thomas Hodge Yearian. Thomas was also from Illinois, and they exchanged quite a few letters in between their shared dances. According to their son, Thomas’s penmanship was impeccable, which must have appealed to the schoolteacher in Emma. Their correspondence blossomed into a romance that would lead to a lifelong love between the two of them, and the Yearians married in April of 1889 and moved into a cabin twenty or so miles up what would later be named Yearian Creek from Salmon.

Despite their love, Emma and Thomas were very different people. He was a born and bred Democrat and cattleman, while she was a staunch Republican and sheepherding pioneer. Ever the disciplinarian, Big Mom would chide her grandson, Ralph Nichols, when he was late for their 6:15 breakfast, saying ‘You’ll never make a living in this world.’ This stands in stark contrast to Thomas**, who remarked that ‘my kids have never disobeyed me, though I’ve been careful never to ask them to do anything they didn’t want to do.’ Emma purportedly hated alcohol and its effects on the body and constitution, even as the whisky flowed freely in the kitchen during their many social engagements. Thomas was also an avid cigar smoker, much to his wife’s chagrin.

When asked how they got along despite their differences, Big Mom would reply simply ‘We didn’t.’ Their seemingly anachronistic tendencies appear to have balanced each other out perfectly. Big Mom handled all the business dealings and financial concerns of their ranch from a ‘rolltop desk crammed full of papers’, while Big Pop looked after the cattle and oversaw the ranch hands.

Between 1889 and 1902, the Yearians welcomed six children into the world, though sadly their youngest son would pass away at the age of 12 from appendicitis (‘our biggest tragedy’). They kept a toy train and a tiny homemade wood saw like they used to cut firewood as remembrances. With a growing family and the arrival of the railroad to Lemhi Valley, it was time to upgrade from their log home to something more modern. Her grandson recalls:

‘About the time the railroad was being built into the Lemhi Valley it looked like civilization was catching up to the frontier and she required a better house than the sod-roofed log building that they lived in. She contacted a stone mason in the east who came out to build a house. Some five miles up Yearian Creek above the ranch there were some sandstone ledges exposed. The stone mason decreed them suitable building material so the ranch crew quarried and hauled by team and wagon enough stones to build. The irregular blocks were then shaped to a specified size and the edges rounded. The stone house turned out to be a very impressive structure, two stories and a basement and porches front and back. There was even a bathroom with a commode and a bathtub. There was no water and that didn’t come until quite a few years later when electricity came to the valley.’

By all accounts, Big Mom was thrilled with the results, excitedly showing off the home to one of the Yearian’s longtime ranch hands. In response, he said ‘Well, insides alright but the outside ain’t no great shakes.’

In a predicament that still rings true today, Emma became concerned about how they were going to pay for all of their kids to go to college. She tried to convince Thomas to replace his herd of cattle with sheep, thinking sheep were better suited to climate and terrain. Thomas was not completely convinced, but he did agree to adding a thousand head of sheep to their cattle concerns. Emma convinced a banker to loan her the money necessary, and she, Thomas, and one of their sons drove the flock from Montana back to their ranch in Lemhi Valley.

Emma received resistance not only from Thomas, but also from the local cattle ranchers that dominated the local ranges. Salmon and Lemhi Valleys had a ‘Two Mile Rule’ that prohibited sheep from grazing within two miles of a cattle herd. This stemmed from a mistaken notion that sheep would eat too much of the grass, making it too short to survive the harsh winter. However, sheep primarily ate weeds and wildflowers, leaving the grass alone for cattle. Emma was often brought to court for violating this law, though she was never convicted, and ‘no one ever pointed a gun at her.’ A major complaint she often heard was that sheep smell bad, to which she would reply, ‘They smell like money to me.’ In spite of the opposition, Emma’s flock thrived alongside Thomas’s cattle, and before long many cattlemen were incorporating sheep into their livestock holdings.

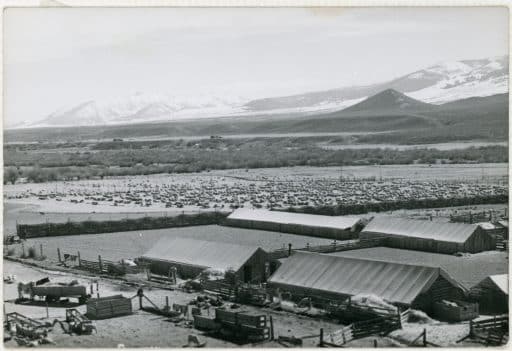

Even before she became active in politics, Emma was very politically aware. She predicted the advent of the first World War, going so far as to seek a second loan to increase wool production for military uniforms well before the first shots were fired. She purchased sheep with extra thick coats ideally suited for this purpose, and made a tidy profit off the war effort. Her shrewd business practices allowed the operation to survive the Great Depression, and by 1933 she oversaw 6,000 sheep spread across 2,500 acres of land. Not only was she inspirational and influential locally, she also published several articles, including a 1920 feature in the American Sheep Breeder and Wool Grower journal about her experience breeding range sheep.

In 1930, Emma became the first woman to represent Lemhi County in the Idaho State Legislature. She was elected as a Republican, which was particularly remarkable for the time given her husband’s opposing political views, and she likely would have won reelection if it weren’t for the widespread national Democratic landslide. Around this time, Emma made a trip to Europe with a group of other businesswomen via train and then steamship, which was a rarity during this era.

When at home, Emma and Thomas were the consummate hosts, leading their house to be dubbed by some as ‘Wait a While Ranch’. With little coaxing, Thomas would break out his fiddle, accompany Emma on her piano, and everyone else would be invited to share their talents. But even when entertaining, their perfectly balanced differences emerged. ‘Big Mom held sway in the living room… in the meantime the kitchen crowd grew more raucous as the alcohol flowed freely.’

Emma continued to tend her flock in person and on foot well into her 80s, before she passed away on Christmas Day of 1951 at the ripe old age of 85. In a turn of events that is sure to have Emma rolling in her grave, Thomas, despite his penchant for cigars and whiskey, lived to ninety nine and a half years of age. May we all be so fortunate.

And thus concludes this telling of Emma Yearian Russell’s remarkable story. From a log cabin to a stone house, school teacher to pioneering sheep rancher to influential politician, from Lemhi County to Western Europe, long may the Sheep Queen of Idaho’s legacy remain.

Thank you to the Lemhi County Historical Society and Museum for use of their images, as well as access to primary source documents, including remembrances from Nicholas Yearian quoted throughout.

*Normal Schools or Normal Colleges were designed to train teachers. The practice rose to prominence in France during the 17th Century and persisted into the early 20th Century. The name is derived from the French école normale, which describes learning in a model classroom with live students and teachers.

**Thomas was reported to have a very good relationship with the local tribespeople, especially the children. His son recalls seeing ‘one little girl running up to grasp his hand and looking adoringly up at him, and softly stated, “Boppa, you ole sumbich.”’